A Review of Eyes Wide Shut

‘I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be, and it’s too late.’ – Martin Scorsese at 83 years old.

Begging the question of what it means to create art in its purest form and how long it takes to find that in our battle against time.

‘Eyes Wide Shut’

The best New York Christmas movie that

wasn’t shot in New York nor about Christmas

My relationship with Kubrick’s body of work is complicated, stretching back to a time when the media I was exposed to was not of my own volition, but of the nerdy cinephile incumbent that was my father. By nine, I had already watched Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, Apocalypse Now, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy (the extended cuts, naturally). And while I was permitted to see Kubrick’s 2001, along with some snippets of A Clockwork Orange, the rest of his filmography was barred from my viewing. Even as a preteen, it was made very clear to me that there was something incredibly taboo about his films.

The door remained shut until this winter. While sheltered in my dorm, acclimatizing to the Northeastern winter in lieu of Californian fall, I decided to watch Eyes Wide Shut. This was Kubrick’s last film, released only days after his death. Some opine that it was an incredibly poignant piece of art which explored the human condition through themes of sex, masculinity, and femininity –while others found it underwhelming, overshadowed by his past projects.

I had gone into the film with little idea of what it was about, having only seen a scene of Tom Cruise walking pensively down a street in New York in the dead of night. Although no more than 20 seconds, the scene lingered in my mind for days on end. Every neon sign and street lamp was incandescent and hazy, coating the picture in an ethereal aura. Kubrick employed techniques of push process/emulsion to overdevelop the lighting and give it that characteristic warm glow. It seemed like every aspect of the film was meticulously crafted to elicit a specific emotion from the viewer.

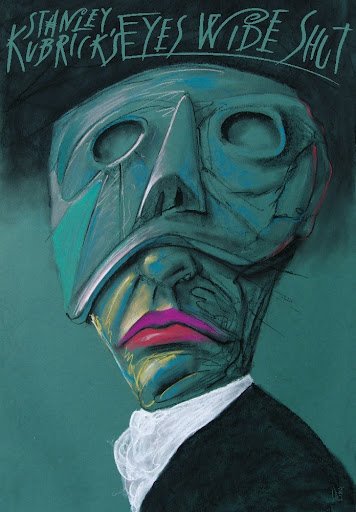

Without giving away too much of the film, the general idea of the story is as follows. A seemingly healthy and stable union is suddenly flipped on its head after an ornate Christmas party at a friend’s penthouse. Well-respected doctor Bill (Cruise) finds out that his wife, Alice, (Nicole Kidman) is having vivid dreams of being unfaithful, which sends Bill spiraling. As he wanders the streets, he runs into an old friend. A bizarre med school-dropout-turned jazz musician who has recently been hired to play piano for a masked orgy. Bill’s morbid curiosity and emasculation at the hand of his wife’s dream get the better of him. After begging his friend for the secret entry code to the party, Bill attempts to sneak in. Nearly immediately, Bill is caught, unmasked, and shamed in front of the rest of the masqueraded partygoers. Ironically, at this party, being forced to take off one’s mask seemed more akin to denuding than the actual act of taking one’s clothes off. Bill spends the rest of the movie driven by paranoia. His pianist friend tells him that these people are incredibly wealthy and powerful, and were more than willing to use their influence to dole out punishment as they saw fit.

The film feels genre-less, not exactly an erotic thriller nor quintessentially Kubrick. He was known for being incredibly anal when it came to how he shot his movies. Since his fear of flying left him sequestered in England, the production crew built a hyperrealistic set of Greenwich Village down to the street measurements. Kubrick’s decision to set it during Christmas was par for the course. Kubrick often relied entirely on source location light. Christmas trees and street lights imbue the scenes with an opulent radiance. Kubrick used Chinese paper lanterns to softly illuminate the shots from behind, further dramatizing the “dreamlike, hazy glow of colored lights and tinsel” (Lee Siegel for Harper magazine). Film critics see these motifs, the Venetian masks, and more obviously the illustrious penthouse and mansion parties as allusions to themes of hedonism, money, and class.

Some argue that the film aims to criticize Christmas consumerism through its wealthy and powerful characters. While Bill is an incredibly affluent and influential doctor, he appears impotent in contrast to his richer patients and friends, like the ones who host the glamorous holiday ball at the start of the film. When Bill is unmasked at the pagan sex cult party, this sentiment is reinforced. And while these two settings are quite literally as different as heaven and hell, Bill occupies the same niche – as do his wealthy contemporaries. The only difference is the way in which they conceal their vices.

After my initial watch of this movie, I was captivated by its eeriness, hell-bent on figuring out all the invisible techniques that Kubrick employed to realize that end. Beyond the watertight writing and dialogue, there is an unparalleled element of visual storytelling (I’ll refer to the short clip I saw online that first caught my eyes). What looked like a dolly shot of Cruise in the city was in actuality rear-projection and treadmill. A video of the set was placed behind the actor as he walked in place, giving it that surreal effect. The result is this strange feeling of the world passing the viewer by. You’re as lost in thought as Cruise’s character, more preoccupied with the ennui clouding your mind than the environment around you. This is one of the many reasons why I love film so much. It’s just so incredible to see this much thought go into the execution of each and every idea. Every creative choice is done so with intent and passion. It leaves the viewer with something more each time they rewatch the film. Even as I write about it now, I’m thinking of all the things I missed on my first pass, and can only imagine the things I’ll notice the next time around.